Following the collapse of Carillion, my colleague, David Springate and I started a project to see if we could help government organisations assess and manage the risks associated with outsourcing. Specifically, whether we could do this by applying data analytics techniques to a sample of open government spend and contract data.

The result was a 3-part blog series. This is the third and final blog post in the series. The first two posts (which you can find here and here) focused on:

-

the process of getting the data we needed

-

how we decided on which ‘business questions’ we needed to try to answer and

-

how we decided on which patterns and metrics would provide the insights that could help answer those questions

In this last post, I demonstrate how the patterns and metrics we discovered lead to insights when applied at organisational data. I also outline some ideas about what it would take to draw to scale the process of generating these insights.

Looking a bit deeper

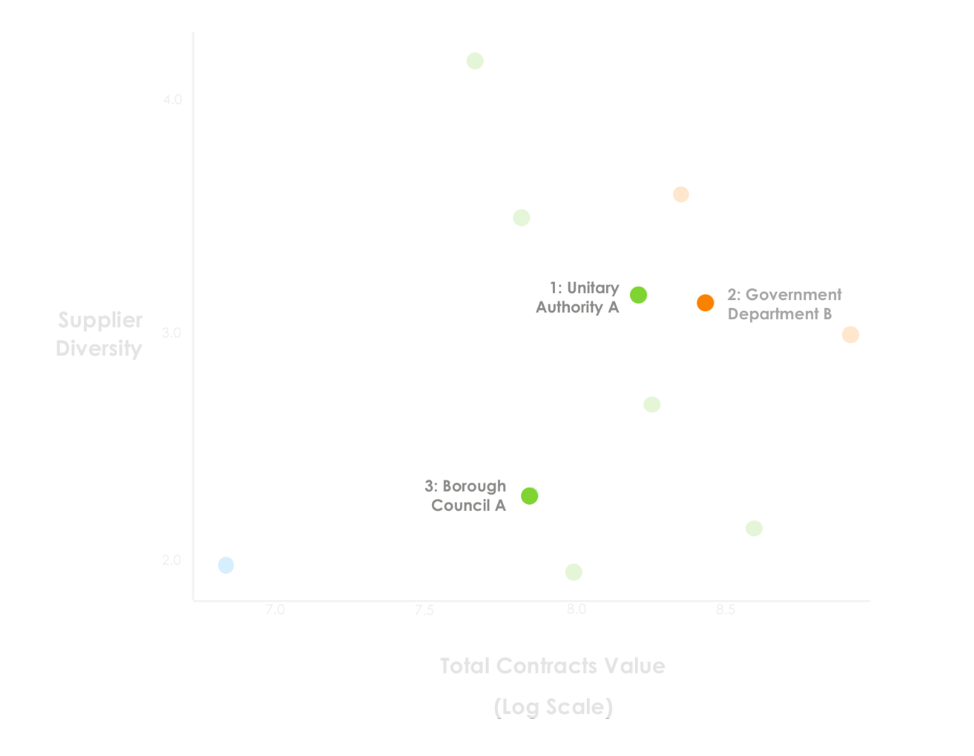

To get a better sense of what this data actually means, it’s worth ‘drilling’ into data. Here’s an outline of the deeper analysis we did into the spending data of 3 government organisations – 1 central government department, 1 southern- and 1 northern-English local authority.

Let’s start with government department B. Over the 6 year period, the department’s budget for the relevant spend categories was £265 million and it contracted with 108 unique suppliers. In 2015 and 2016, the department spent most of this budget 33% and 55% (i.e. £10.4 million and £11 million) respectively with one supplier.

Let’s start with government department B. Over the 6 year period, the department’s budget for the relevant spend categories was £265 million and it contracted with 108 unique suppliers. In 2015 and 2016, the department spent most of this budget 33% and 55% (i.e. £10.4 million and £11 million) respectively with one supplier.

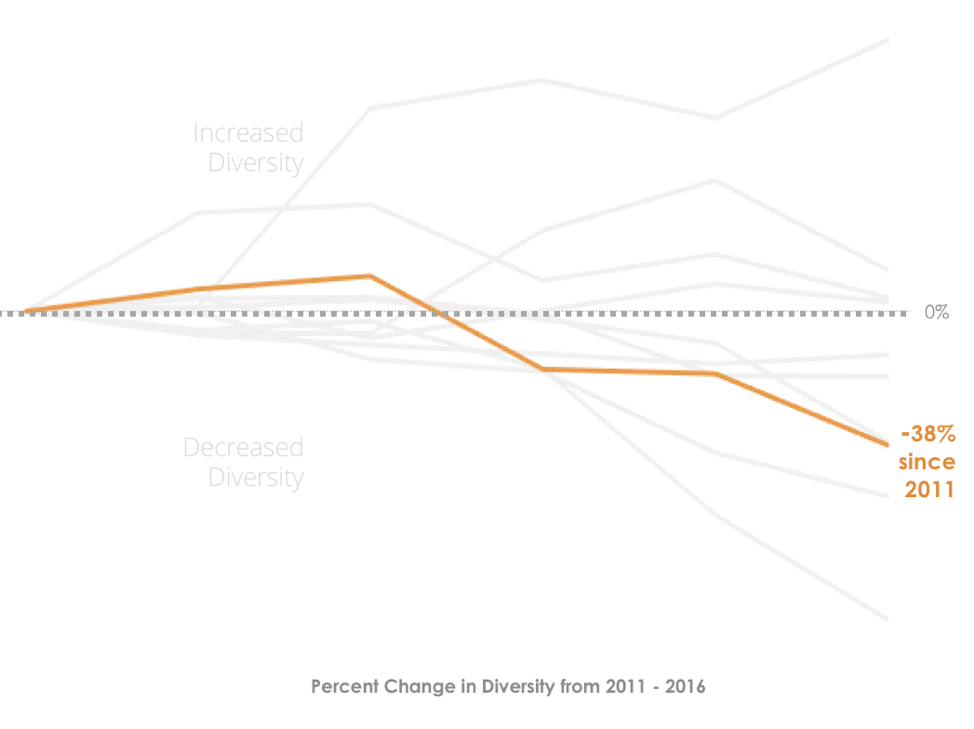

But back in 2012, the same supplier was awarded contracts worth only 10.1% of the spend (i.e. £7.9 million). So there was a drop in evenness over the period. There was also a drop in the number of contracted outsourcers. This means diversity also fell – making it harder for the department to switch to alternative providers in the event that one of its outsourcers failed.

This is even more interesting given that the department was highly consistent in the services it outsourced, meaning that its change in approach is unlikely to have been necessitated by a need for services that were especially difficult to procure. In other words, the department appears to have procurement decisions that reduced its ability to leverage competition in the market.

-

On the whole, the evenness of Unitary Authority A’s spending was relatively consistent over the period under review. The same top supplier accounted for 44% (£10.6 million of a budget of £24.4 million) in 2011 and 48% (£9.3 million of a budget of £19.4) in 2016. It did show a steady decline in the number of suppliers over time from a peak of 327 unique suppliers in 2012 to a low of 71 in 2016. So spending became less diverse over time.

The impact of this drop in diversity is difficult to assess. However looking into the services that the authority procured between 2012 and 2016, we see a high degree of consistency and at the same time a high degree of churn between the suppliers who provided these services.

This suggests the suppliers were highly fungible. It’s reasonable to infer that it’s easier for the agency to swap one out for another thereby reducing ‘lock in’ and making it easier to manage the effects of an outsourcer going bust.

In 2014, for example, the top supplier accounted for approximately £560,000 from a total budget of £2.4 million. During this time three different suppliers took the top spot – suggesting limited lock-in. But at the same time, the local authority saw a decline in the number of suppliers from 231 in 2011 to 126 in 2014.

The spending pattern changed significantly in 2015, not only did the council spend more in these categories, they spent 83% (£15.2 million of £18.4 million) of it with a single supplier. In 2016, a different outsourcer accounted for 84% of the budget (£29.4 million of £35.2 million). This seems odd until we delved into the type of services the authority was outsourcing.

Between 2011 and 2014, the authority procured the same services pretty consistently, year on year. But in 2015 this changed drastically and this new focus carried on into 2016. It may well be that there were simply fewer outsourcers capable of supplying these new services and the authority simply had fewer options. This, coupled with the change in focus re the sort of services that the authority chose to outsource could help explain the big drop in the total number of suppliers (from 126 to 75) the government did business.

Consequently, there was a further decline in diversity in spending from 2014 levels. Delving into the data revealed that this single outsourcer was tasked with supplying services as varied as waste collection and advising on flood risk through to maintaining the town’s Christmas lights! This raises serious questions about how the council’s ability to manage the impact of supplier failure.

In conclusion: what we learned and why it matters

Data analytics helps ensure that useful patterns and insights, within the data that’s available, are identified and available to support decision-making. This is an important point because it is often the case that we don’t have all the data we need to directly answer all the questions we have. Skilful analysis and inference are useful in such cases - but even when they don’t answer all the questions we have, they do help us identify where to investigate further.

The procurement teams of the 3 government organisations we considered above, might want to dig deeper into:

-

the reason behind the government organisations’ decision to outsource services to fewer suppliers. It might be financially motivated, for example - it could be because the outsourcer they went with offered them a discount. Our dataset doesn’t include suppliers’ tender data so we’re not able to make an inference about this from the data

-

whether government organisations have the right mix of interchangeable outsourcers. This is hard to determine definitively because classifications weren’t applied by the government organisations themselves, so we’re dependent on those applied by Spend Network.

-

the possible human impact of ‘outsourcer failure’. This is an important consideration when making procurement decisions. For example, an organisation might, on balance, decide that for relatively low impact services, they’re willing to take on the higher level risk (of supplier failure) associated with using fewer outsourcers to gain a price discount.

Making data analytics work for everyone

This exercise gave us the opportunity to identify patterns in government procurement. It also allowed us to explore a proactive approach to reducing government organisations’ exposure to the negative effects of an outsourcer failing. Finally, it provided useful insights that could help procurement specialists in their efforts to continuously refine their procurement processes.

However, the exercise also revealed how much work goes into collecting, preparing and analysing the data in order to glean the insights that decision-makers find helpful. It’s unlikely that most government organisations will be inclined to run such projects on an ongoing basis. And yet, that’s exactly what’s needed if government’s procurement decisions are to keep pace with the continually changing ways that modern organisations provide, lease and buy goods and services.

So how can government make these insights available to the widest number of business users? A centrally-provided, cloud-based analytics platform is one way of doing this. And there are benefits beyond the obvious value that would accrue from making it easy for procurement professionals to interrogate their own organisations’ data, bringing their contextual knowledge and expertise to bear.

It would, for example, make it possible for them to see how their approach to procurement compared with similar organisations, in relevant categories. It would also help politicians and central government teams in their efforts to manage the sort of cross-government coordination activity that the Cabinet Office had to undertake in the wake of Carillion’s collapse.

Lastly, this analytics-as-a-service offer is the sort of reciprocal value exchange that could incentivise government organisations to improve the quality and timeliness of the spend and contract data they publish. At present, much of this publishing is simply a reporting overhead for these organisations, access to data analytics insights could turn data publishing into an investment.

If government is serious about becoming more data-driven then investing in its ability to deliver analytics-at-a-scale in order to better manage its multibillion pound procurement budget, is a good place to start. And that’s something Teradata can help with.

Ade is a Senior Consultant at Teradata, with a focus on Public Sector organisations and their effective use of data. Prior to her role at Teradata, Ade worked at the Government Digital Service (GDS), the organisation created to drive the transformation of UK government content and services through better use of digital technology and data transformation, based in the centre of Government. Ade spent 7 years working across a number of policy, strategy and delivery roles. She went on to lead the implementation of one of its core elements – common data infrastructure- in her role as Head of Data Infrastructure. In this role Ade focused on understanding the needs of users (within and outside) of government data and building a range of data products designed to meet those needs.

Prior to GDS, Ade worked at Nortel, a telecoms equipment vendor. While at Nortel, Ade worked in a number of roles and across a number of areas including product acceptance testing, sales and design and representing Nortel at international technical standards bodies such as 3GPP, IETF etc. These roles gave her a really good understanding of clients’ business needs as well as the commercial and strategic drivers for them, and the value of the right technology for meeting those needs.

View all posts by Ade Adewunmi